Nobel Laureates in Particle Physics by Country

Yunjie Yang

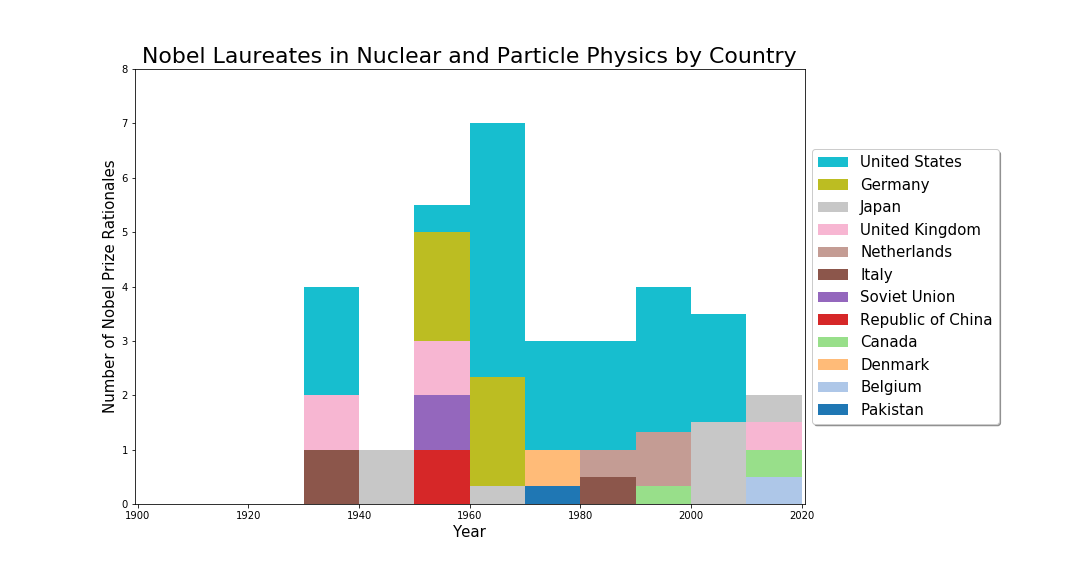

First, what I mean by "country" exactly. This information is directly taken from the Wikipedia page List of Nobel laureates in Physics . There's a footnote for this: "The information in the country column is according to nobelprize.org, the official website of the Nobel Foundation. This information may not necessarily reflect the recipient's birthplace or citizenship." Therefore, I do not guarantee the accuracy of this information, although I regard it as a good approximation to the information that this plot is trying to convey.

Second, the y-axis label reads "Number of Nobel Prize Rationales". By rationale I am referring to the reason that the Nobel committee gives to why they confer the prize to the recipient(s). And here, importantly, I count one rationale as one prize. If there are two (or more) recipients for one rationale, the prize is evenly distributed to each one of them, for simplicity reason (I could do a better job by looking up the prize share each year and do it that way, but I couldn't be bothered to do so). Moreover, if there are more than one country listed for a recipient, the prize of that particular recipient's share is evenly distributed to each listed country.

To give a concrete example, the 2008 prize is quite illustrative. In 2008, there are three recipients and two rationales. Therefore, I will count a total of two prizes from year 2008. For Kobayashi and Maskawa, they share one rationale for their contribution to the quark mixing matrix (the so-called CKM matrix) that bears their names. Hence, they each get 0.5 prizes. Since there's only one country, Japan, for both of them, Japan gets 0.5 + 0.5 = 1 prize from this rationale. The third recipient of this year is Nambu for his contribution to the mechanism of spontaneous symmetry breaking which resulted in particles that bear his name (Nambu-Goldstone bosons). Since he's the only recipient for this rationale and he has two countries listed, Japan and United States each gets 0.5 prize from this rationale. Therefore, Japan got 0.5 × 3 = 1.5 prizes and United States got 0.5 prizes from year 2008. I should say that there's no particular reason or justification for choosing this system (maybe "I wanted to learn how to make weighted and stacked histograms in python" counts as a reason?), but I think it makes sense to me and doesn't change the big picture.

All that said, the plot itself is pretty simple. First, you notice that the first prizes came in the 1930s because my counting of proper particle physics prizes started with the discoveries of positrons and neutrons. One could certainly argue that early developments in quantum mechanics, such as Planck's prize in 1918 and de Broglie's prize in 1929, were crucially important for the emergence of particle physics, but they also laid the foundations for all branches of modern physics, so I decide not to include them for this particular plot. With that said, we now take a look at these unambiguous particle physics Nobel prizes. One can easily see that the structure of the "golden days" of particle physics from the 50s to the 70s is obvious. This is the period of them when a lot of particles and symmetry rules were being discovered and the coherent picture of what we now know as the Standard Model of particle physics was being put together with theoretical framework being completed in the late 60s. The US dominance from 1960 on is also obvious, although there's no U.S. particle physicists that earned a Nobel Prize in this current decade, yet. There's still one year to go.

It is interesting though to see a seemingly slowing-down of total prizes awarded to particle physics. However, with profound questions such as the nature of dark matter, the strong CP problem, the hierarchy problem, baryon-antibaryon asymmetry, neutrino masses, Majorana or Dirac nature of the neutrinos, CP phase in the neutrino-mixing matrix and so on, the field undoubtedly holds tremendous potential for paradigm-shifting discoveries. We just need to find the right lamp post to shed light on the known unknowns, and potentially unknown unknowns, to open up a new era of discoveries that will transform our human beings' understanding of fundamentals of the universe.