Time lag between the experimental discovery and the conferral of the prize

Yunjie Yang

The shortest time lag champion goes to the 1957 Nobel Prize to Lee and Yang with the lag less than a year. Motivated by the so-called ϑ-τ puzzle, Lee and Yang made an important observation that despite ample evidence for parity conservation the in strong and electromagnetic interactions, there was no evidence, surprisingly, neither for nor against, the conservation of parity in the weak interactions. They submitted their paper in June of 1956, talked to their colleague C.S. Wu, who quickly and elegantly set up the famous Wu experiment and found, over Christmas of 1956, that parity is violated (maximally, in fact) in the weak interactions! Because this discovery was such a huge surprise at the time, Lee and Yang were awarded the Nobel Prize in October of 1957, which was less than a year from the experimental discovery!

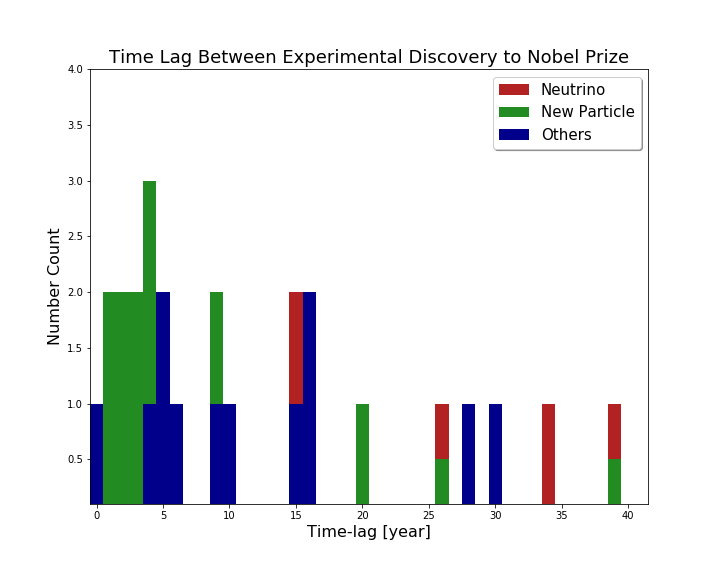

Both the second and third places go to the crucial components in the spontaneously broken electroweak sector: the W and Z vector gauge bosons in 1984 and the Higgs boson in 2013. These two were perhaps particularly unsurprising because they both had been anticipated for so long before their experimental discoveries. In fact, the green components show all the prizes that were awarded due to discoveries of new particle(s), for which time lags were quite short -- mostly less than five years!

However, there's an important and intriguing exception to that -- you typically don't need to wait long to get a Nobel Prize if you discover a Nobel-worthy particle, unless it was a neutrino. The first ever detection of neutrinos (electron antineutrinos to be more precise) was made by Cowan and Reines in 1956 but Reines' Nobel Prize came only in 1995, almost 40 years later (Cowan had passed away by 1995). The detection of muon neutrino, proving that there was more than one flavor of neutrinos, was made by Lederman, Schwartz and Steinberger in 1962 but they had to wait for 26 years to get their Nobel Prize for this work in 1988. Moreover, it simply seems unfair that any neutrino-related Nobel-worthy so far had to wait quite long to get accredited. Ray Davis had to wait for 34 years for the detection of solar neutrinos and even the shortest time lag among the neutrino-related prizes had Kajita and McDonald wait for almost 15 years before they were awarded for their monumental discoveries of neutrino oscillations. Hopefully, this trend is going to change soon. Any of the major themes in neutrino physics nowadays, be it the measurement of the absolute mass scale of neutrinos, or the search for neutrinoless double beta decays, or the determination of the CP phase in the neutrino mixing matrix, holds great potential for Nobel-worthy discoveries that will lead to a hopefully much shorter lag time.